Drone Airworthiness: A missed Opportunity in waiting?

Introduction

India has the biggest pool of talented workforce in the current technological era. However, our workforce is primarily utilized in an outsourcing service model.

In the last few decades, India has missed multiple opportunities to become a world leader in aerospace, medical devices, energy, defense, and many other domains. Outsourcing has facilitated growth in IT service, Automotive, and E-Commerce sectors. The outsourcing model does not necessarily make us self-reliant or product leaders. Moreover, our workforce would be working on the development of foreign products (where Intellectual property will not be with us) and services in contrast to achieving self-reliance in key technologies.

Drone /UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) is one of the key areas where India could demonstrate its capability as a world leader. There is a huge demand for drones in non-military civilian domains (agriculture, Industrial, crowd monitoring, medical (tracking the gathering for maintaining law and order situation and spreading sanitizers are the two usages which are observed during COVID lockdown) and other ) apart from the legacy requirements for military drones.

However, the drone regulation framework in India is not evolved compared to the USA/EU and we could see some traction in guidance in classification, registration and operation. Even if the progress is encouraging but it is our first baby steps towards a holistic regulatory framework specifically in the civil airspace for commercial applications where safety and security are of utmost importance. This paper would discuss military/non-military drone market, existing Digital Sky structure and a proposed regulatory framework along with airworthiness aspects.

Legacy of Military UAVs in India

India has been one of the top importers of the drone for the past many years for both military and civilian usage as per one forecast by Statista.

Let us explore India’s UAV/drone journey so far starting from military UAVs to non-military/commercial UAVs.

DRDO (Defence Research and Development Organisation) has been at the forefront of Military UAV development in India. Some of the successful projects designed and developed by DRDO are:

- Lakshya: Lakshya is a cost-effective, re-usable high subsonic, advanced Pilotless Target Aircraft (launched by a solid-propellant rocket motor, sustained by a turbojet engine in flight, and is recovered with an aero conical parachute and impact attenuation system) and is a target for weapon systems like radar-guided and heat-seeking Surface to Air missiles, Air to Air missiles. Lakshya Weapon Delivery Configuration is also being developed for weapon delivery like high energy weapon, ballistic, unguided weapon payloads at known Coordinates. Lakshya could be configured for discreet aerial reconnaissance.

- Nishant: Nishant is a multi-mission Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (launched using a mobile hydro-pneumatic launcher and has a similar recovery mechanism) with Day/Night capability used for battlefield surveillance and reconnaissance, target tracking & localization and artillery fire correction. Nishant has completed user trials and is inducted in the Indian Army.

- Rustom: Rustom (with conventional take-off and landing capability) is adapted after USA UAV Predator. It is all-composite, Short Range Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (SR-RPAS), medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) with autonomous flight mode and get-to-home features with capabilities of intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, target acquisition/ tracking and image exploitation. Additional features like automatic take-off and landing (ATOL), synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and Store carrying capability are considered for future implementation.

The Rustom is still in the development stage and is expected to replace and supplement Israeli Heron UAVs and others in the Indian Air Force.

Other noteworthy UAVs are Imperial Eagle (IE), a mini UAV designed and developed by a joint effort of DRDO and CSIR-NAL; Netra, a quadcopter designed and developed in collaboration with ideaForge.

Military UAV Import

The DRDO has limited success with small and medium UAVs (less than 150 Kg) but the need for the armed forces is not catered, and it is unlikely a project worthy of latest combat and stealth capabilities realized shortly. Armed forces have constrained to import military UAVs to augment strategic capabilities to counter hostile neighbouring environment.

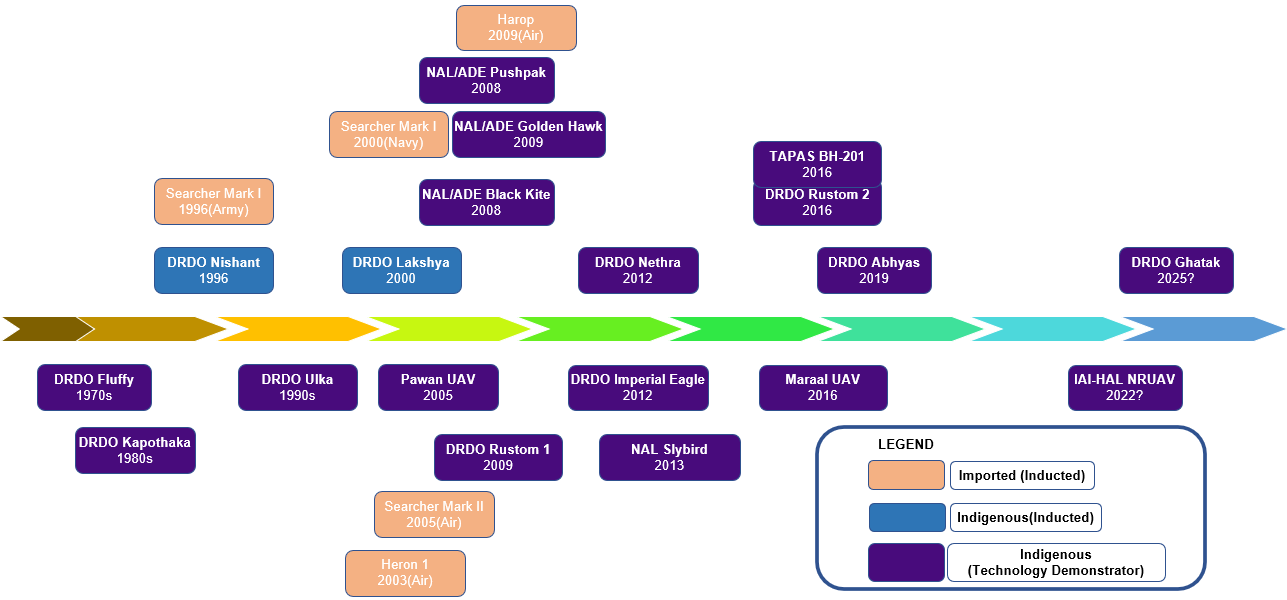

Armed forces (Army, Navy, and Air Force) have inducted Israel-made drones IAI Searchers (I and II), Heron for surveillance and reconnaissance missions. Besides, IAF also fields a fleet of IAI Harop drones, a self-destruct drone carrying a high-explosive warhead and primarily used for targeting enemy radar stations. Please refer to Figure 1 for the military drone development and induction timeline.

Figure 1 Timeline of Drone/UAV induction

Non-military drone application in India

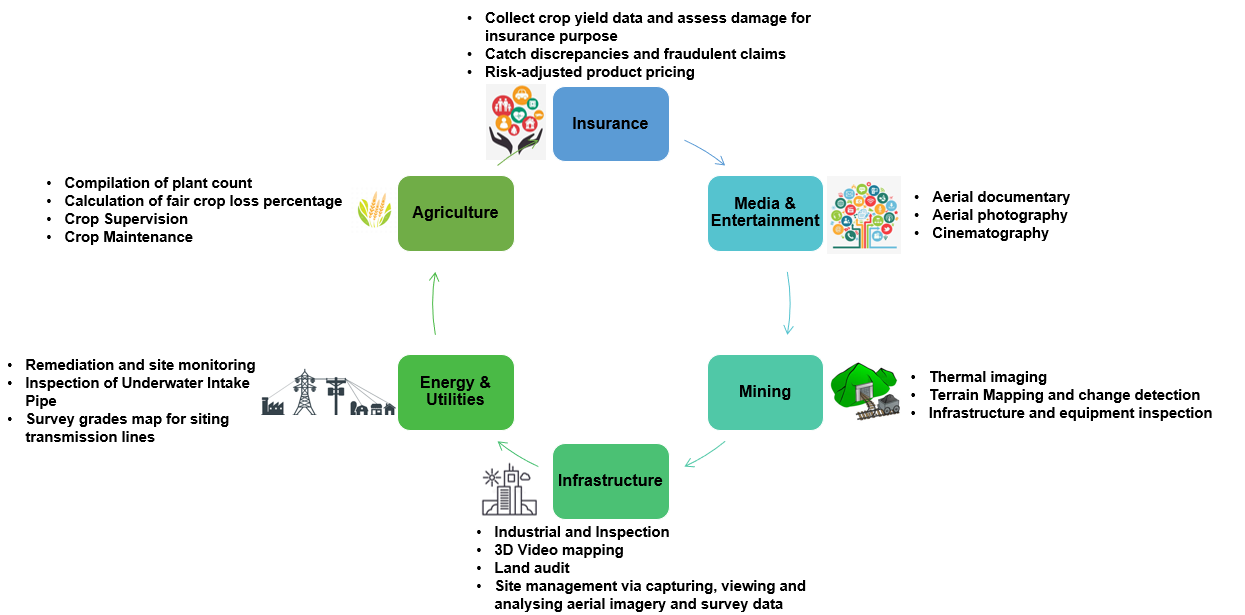

The non-military drone applications are typically are in infrastructure, agriculture, transport, security, media and entertainment, insurance, telecommunication and mining.

Figure 2 Various non-military drone application (Source: PWC)

The drone startups and private players have established their solid presence in the ecosystem. They are primarily catering to non-military space. As per research, the total funding raised by drone startups in India was $16.56 Million (from 2014 to 2018), though the amount could have been many times higher, nevertheless, the investment will increase.

IdeaForge, Asteria Aerospace, KADET DEFENSE SYSTEMS, CROM Systems, and AADYAH Aerospace are the key players in military UAVs. DETECT Technologies, Bubblefly, Aero360 and Quidich are other sets of players that are active in commercial drones.

A proposed drone regulatory framework

Figure 3 A proposed drone regulatory framework (Source: www.droneii.com)

A typical drone regulation framework would consist of applicability for industries and associated regulation, operational limitations, human resources, administrative infrastructure, airspace integration, and Social acceptance aspects.

In India, globally accepted regulations and standards are not adopted or complied either for indigenous or imported drones. The prime goal has been achieving the desired functionalities and requirements of armed forces.

Drone regulation is a multi-disciplinary, complex framework. As most of the commercial drones are imported, DGCA (Directorate General of Civil Aviation), has emphasized the regulation related to registration, operation, and training. In the past when drone imports have surged, DGCA placed a temporary ban on imports from 2014 to 2018. It is ironic, DGCA, BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards), and other government regulators did not come with any concrete, usable regulation for drones. This hiatus pushed the drone industry into confusion.

Ministry of Civil Aviation published regulation of drones(Aug 2018), Airport Authority of India (AAI) published AIP (Aeronautical Information Publication) supplement 164 (on Nov 2018), DGCA came out with RPAS requirement (on Dec 2018), initiated Digital Sky platform launch (Dec 2018), drone policy Roadmap (Jan 2019) and drone registration through digital sky initiatives (Jan 2020).

Digital Sky Platform implements 'no permission, no take-off’ (NPNT) policy, facilitates Unmanned Aerial Operator’s Permit (UAOP) and Unique Identification Numbers (UIN) registration.

Figure 4 Drone Regulation Timeline

We have achieved partially the objectives of operational limitations, human resources, administrative infrastructure.

There would be a need for integrated airspace where drone movement would be monitored, managed and ensured there is no breach of airspaces (civilian drones getting into the airspace of commercial flights, restricted airspace, critical infrastructure or violating the privacy of individuals). In many nations, shooting down, spoofing and hacking of airborne drones are illegal and need to be dealt with differently. It includes tracking the drones by its unique RF identification (friend or foe), coordinating with the designated drone operators before taking any drastic measures.

The applicability of the drone standard/law/regulation for the various stakeholders is to be explored fully.

Social acceptance of drones should address privacy, data protection, and liability law/regulation arising due to drone use/misuse.

Figure 5 How Digital Sky Works? (Source: https://factordaily.com)

Digital Sky is an online IT platform developed for handling UIN, UAOP applications, permission to fly RPAs in India.

Digital Sky framework would probably enable the manufacturing process, operator process, online process (flight path permission with geofencing, offline process (take-off procedure), flight logging (flight plan uploading), and incident reporting (crash, incursion). On the outset, the framework looks promising, however, each stage and activities will manifest into complex processes, and clarity would be needed.

Consider a simple case, how DGCA will track so many drones, do they only rely on the where it is, the information of drone from the operator(what would be the latency of the position update), can drones declare their position like ADS-B(Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast), will DGCA or airport maintain radar(passive or active mode) to detect the drone, if active tracking is required will drone operators share their RF/protocol details. If the drone is encroaching (controlled or uncontrolled way/loss of control) in a restricted area, what actions are to be carried (shooting down, spoofing, jamming) out.

Airworthiness

The airworthiness considerations in the applicability and administrative infrastructure aspects are neglected in India. Probably it is assumed the drones are inherently safe and secure and government agencies only considered operational and training aspects of drones.

This situation could be attributed to the lack of cohesion and initiatives from the policymaker/regulator to formalize or adopt international standards /guidelines from the nodal agencies and prolonged indulgence in the operational aspects of drones.

Airworthiness can be achieved by compliance-based standards, guidelines, and regulation along with risk-based standards/guidelines. The Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) model is endorsed by EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency) for drones and it consists of a ground risk class (GRC) and an air risk class (ARC). The outcome of the assessment (while considering the safety and security factors) would lead to safety and security objectives and further decomposed into requirements.

Figure 6 Risk-Based (Safety and Security) Airworthiness framework

Also, sub-systems like sensor systems, navigation systems, flight control systems, landing systems, communication systems and application-specific systems (Camera, Radar, Delivery system) would go through the rigour of airworthiness approval as per appropriate international standards or guidelines.

Software Aspects of Airworthiness

Figure 7 Error propagation leading to Hazard

The drone system is a blend of multiple subsystems like flight control, communication, landing system, power, and other systems. Complex embedded software in the sub-system manages the functionalities and interaction with other systems. Software-based hazard, threat (vulnerability) assessment should also be carried out to confirm that software error is not manifested to a hazard. Besides, the complete system needed to be verified on the system (black box), module and component(unit) levels.

LDRA tool suite® provides adherence to safety/security coding guidelines, testing framework, and consulting service to assist in risk assessment, standard compliance and liaisoning with the regulators.

Airworthiness Framework

A typical airworthiness regulatory framework (from FAA) could be found in Figure 8. However, even the frameworks are for commercial drones, these are well suited for military drones too.

However, these frameworks are complex and time-consuming to implement, adhere, and sustain in the Indian scenario where the aerospace certification ecosystem is not evolved. Besides, getting subject matter and certification experts on the complex airworthiness topics are infeasible. These frameworks are more suited for Large and Medium types of drones.

Figure 8 Airworthiness framework(USA/FAA based framework)

Micro and Small drones probably need a relaxed, moderately complex and usable airworthiness framework based on consensus standards from IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), ASTM (formerly known as American Society for Testing and Materials), and SAE (formerly known as the Society of Automotive Engineers). BIS has initiated activities for standardization in drone design and airworthiness. However, adopting ISO, IEEE standards are the initial steps but there would be multiple considerations (avionics, airworthiness, training, airfield integration and others) to devise a regulatory/compliance framework.

The other consideration like social acceptance which is associated with privacy and liability perhaps would be taken on priority by the regulator.

Figure 9 A proposed set of standards for Micro and Small drones

Conclusion

Operational aspects are one part of the jigsaw puzzle of the complete drone ecosystem. Design of avionics, sensor equipment to acceptable standards will aid in a quicker approval process. If the drones comply with consensus-based international standards, India suppliers could export and could establish their presence in domain-specific Micro and Small drones. Large and Medium drones would typically fit into the military domain, wherein stringent airworthiness process is warranted for the design and acceptance phases irrespective of the source of origin (indigenous or imported).

The recommendation for drone airworthiness (for India context) would be a mix of compliance guidelines from the agencies (DGCA, BIS) and adherence of consensus-based standards. BIS has kick-started TED-14 (Sub Committee on ‘UAV Systems’) in 2020 to bring the stakeholders to harmonize drone standards for the Indian context. LDRA has been an active member of this committee providing their insight into software aspects of airworthiness.

Probably it would be prerogative of the agencies to define the appropriate, acceptable standards through collaborating multiple stakeholders comprising global industry players, academia, certification body, Civil Aviation Authority, regulator and others.

How LDRA could help

As part of the certification ecosystem for all safety security, and mission-critical product development, headquartered at Liverpool-UK, LDRA has been the pioneers and instrumental in many of the process & functional safety standards and coding guidelines since 1975. LDRA assured world-class tools and capabilities in certification make us the preferred ecosystem partner for most of the industry verticals.

LDRA has supported drone/UAV and UAM (Urban Air Mobility) projects with LDRA tool suite® and consulting services and would aid the Indian drone industry to achieve its objectives.

References

- https://dronecenter.bard.edu/drones-in-india/

- https://www.drdo.gov.in/pilotless-target-aircraft-lakshya

- https://www.drdo.gov.in/lakshya-2

- http://www.orbat.info/cimh/special%20articles/Lakshya_PTA.pdf

- https://www.drdo.gov.in/nishant

- https://www.pwc.pl/pl/pdf/clarity-from-above-pwc.pdf

- https://thediplomat.com/2015/09/indias-air-force-to-get-10-killer-drones-from-israel/

- http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/unmanned-platforms-in-the-iaf-the-need-to-bolster/

- https://www.indiastrategic.in/topstories1369_Unmanned_Aerial_Vehicle.htm

Citations

1. https://www.statista.com/chart/20005/total-forecast-purchases-of-weaponized-military-drones/

2. https://www.drdo.gov.in/unmanned-aerial-systems-uas

3. https://www.pwc.in/consulting/financial-services/fintech/fintech-insights/data-on-wings-a-close-look-at-drones-in-india.html#sources

4. https://www.pwc.pl/pl/pdf/clarity-from-above-pwc.pdf

5. https://pages.inc42.com/wp- content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/05/Drone_Technology_Report_2019-1.pdf

6. https://www.droneii.com/drone-regulation

7. https://dgca.gov.in/digigov-portal/?page=civilAviationRequirements

8. https://aim-india.aai.aero/sites/default/files/aip_supplements/AIPS_2018_164.pdf

9. https://public-prd-dgca.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/InventoryList/headerblock/drones/DGCA%20RPAS%20Guidance%20Manual.pdf

10. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186069

11. https://www.globalaviationsummit.in/documents/DRONE-ECOSYSTEM-POLICY-ROADMAP.pdf

12. https://www.civilaviation.gov.in/sites/default/files/Drone_Registration_Public_Notice_13012020.pdf

13. https://factordaily.com/indian-digital-sky-system-for-drones-takes-shape/

14. A definition of airworthiness can be found in an Italian RAI-ENAC Technical Regulation Text: For an aircraft ,or aircraft part,(airworthiness) is the possession of the necessary requirements for flying in safe conditions, within allowable limits.